Last week we posted the first part of a series focused on recollections of reporting during the 2007 Saffron Revolution, and discussion of the state of media freedom and society in the country today. This week, Notebook interviewed Than Lwin Htun, VOA’s Burmese Service Chief.

Than Lwin Htun was recently in Burma, where he conducted an exclusive interview with Burmese President Thein Sein.

___

August/September 2007: Covering Burma’s Saffron Revolution [part 2], a Q&A with Than Lwin Htun, VOA’s Burmese Service Chief

Q: What was your most memorable moment covering the Saffron Revolution in 2007?

A: A group of Buddhist monks marched to Suu Kyi’s residence where she was under house arrest. I remember it because one of our stringers followed the group of monks and was occasionally reporting to us what was happening. The securities and policemen tried to prevent the monks from reaching Suu Kyi’s residence, but later on, they allowed the group to go on. Suu Kyi suddenly appeared at the gate. It was the first glance of her in years. It was a confusing but exciting moment for us. I vividly remember the scene because we haven’t seen her for ages. The situation was quite tense in the beginning.

Q: What was VOA’s role in Burma in 2007? Have you seen that role change from 2007 to today?

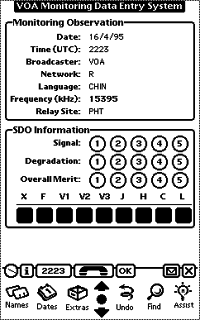

A: There was an information and communication blockade by the authorities. People in Burma have no way to know what was happening outside of their township even in their neighborhood so they relied on us as an international broadcaster.

2007 was also the year where citizen journalism in Burma emerged. People started taking charge by using mobile phones to take evidence of what they saw or witnessed and tried to convey their message via us or the internet. I feel that the way of passing information in Burma changed and this has continued today.

Q: Five years ago, could you anticipate the changes that have happened in Burma this year?

A: No. the changes in Burma are unpredictable and most of the time, very sudden. For example, until September of 2011, VOA was portrayed as a public enemy on the back page advertisement in the national newspapers. Suddenly, that disappeared in October 2011, and in November 2011 I had a chance to go back to Burma and talk to the Burmese authorities. It was the first time in 24 years in my life that I went back to Burma. My work as a journalist, first at BBC, and then at VOA prevented me from going back previously.

Q: What is your view of the state of media freedom today in Burma?

A: Recently, Burma has abolished its censorship board that used to scrutinize all of the press. However, censorship remains to some degree, because media has to go through a kind of self-censorship due to the looming threat of legal actions. People are saying they must take responsibility for what they write. For example, there is a case of the government ministry suing a newspaper for its coverage of officials’ corruptions, or sometimes newspapers are banned for a few weeks because some of their news coverage upset the authorities. And Burma still does not have privately owned independent daily newspapers, nor independent radio/TV stations apart from weekly news journals.

For more information about VOA’s Burmese service, you can visit their blog, which features photos and a behind-the-scenes look at their work!